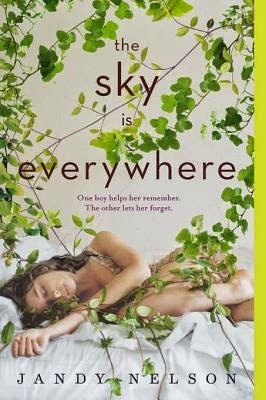

Jandy

Nelson’s I’ll Give You the Sun blew

me away. She writes in high-definition. It’s more than highly developed characters

you care about. When Jandy Nelson writes

it’s in color, and almost everyone else is in black and white. Reading Nelson is like walking into Wonka’s

chocolate factory and it’s not just a mirage –you can walk into it and touch

everything and taste it. I tried tearing

apart what Jandy Nelson had done to achieve this, but it wasn’t until I read another

nameless new novel that I fully understood some of what Nelson is doing when

she writes. I finished the fifth chapter

of Nameless Novel breathless, about to start telling people I wished I had

written this book. The premise was out

of this world. But it is way too easy to

post-it pages that let me down. Though

each of these four post-it points deals with a slightly different writing craft

principle, I suspect they are all negative examples of what Jandy Nelson does

so well.

Stage It

I had

the distinct feeling that Nameless Author was using her characters to move the

reader through her own thoughts. Too

often scenes weren’t about characters in conflict over their desires. Instead, the author uses her characters as

puppets to walk us through her own line of thought. The result is the characters do not sound

like young people, nor do they sound distinct from each other. The dialogue reads as hokey and fake. I am so much more present in the author’s head

than I am in the novel’s scenes, scenes which could have been dripping mood and

tense with conflict.

Her

ability to stage characters’ essential discoveries through action is perhaps

Nelson’s greatest strength as a writer.

The most memorable occasion in I’ll

Give You the Sun occurs on page 308:

It’s time for second chances. It’s time to remake the world.

Knowing I only have one shot to get it right with

this tool, I wrap the cord around my shoulder, position the circular saw

between Noah’s shoulder and my own, and turn on the power. The tool roars to life. My whole body vibrates with electricity as I

split the rock in two.

So that NoahandJude becomes Noah and Jude.

Jude splits her sculpture

down the middle epitomizing her need to be a whole person separate from her

twin brother. She could have just said

this in a line of dialogue, but as an action the moment is heightened,

beautiful, and memorable.

Emotional Core

Nameless

Author often dangled potential scenes in front of me only to snatch them away

and avoid them entirely. Two main

characters discuss a move on of them has to make. No sooner does one of them reflect, in her

head, how hard this will be, than we skip ahead to the next scene, a scene in

which the significant move has already been made. The reader never gets to see the scene

happen. I felt so cheated. I wanted to see this experience in a

scene. As a reader, I want to head

directly into the characters’ messiest, most emotionally challenging, horrific

moments. I want to head into the moments

that deal directly with the emotional core of the story.

In

contrast, Nelson’s Noah has just been caught masturbating with Brian, caught by

his mom. “She doesn’t pretend it didn’t happen,” Noah

says narrating the opening of the next scene, and neither does Nelson. She lays down sentence after sentence heading

directly into the messiest of moments, the one Noah would most like to avoid,

and –oddly enough –one right at the emotional core of the novel. As Dianna enters Noah’s room to talk about

what happened, I wriggle in my chair squeamishly. I want to get out of this scene as much as

Noah does. But Nelson steers us right

through it, and her courage results in fabulously real moments like Noah’s

exclamation:

How does she know what I’m feeling? How does she know anything about

anything? She doesn’t. She can’t.

She can’t just barge into my most secret world and then try to show me

around.

And the scene ends with

Dianna’s theme-cracking statement to Noah:

“Listen to

me. It takes a lot of courage to be true

to yourself, true to you heart. You

always have been very brave that way and I pray you always will be. It’s your responsibility, Noah. Remember that.”

And, yes, that cuts right to

the core of Noah’s conflict with his mom and, more importantly, himself.

Character Development & Stakes

Namelss

Novel’s protagonist loses her closest friend to a decision she, herself, will

soon have to face. Nameless Novel’s

protagonist witnesses the loss, she sees it happen, and it is final. This should be a climactic scene in the book. The protagonist, already dealing with

traumatic loss, stands to lose the first person she’s trusted to be a real

friend. But the scene leaves me

cold. Why? The lost friend is severely

underdeveloped. She doesn’t feel

distinct from the protagonist as a person.

She doesn’t even speak differently.

She is characterized differently in terms of interest, background, and

even race, but on the level of the soul, her approach to life has never been

given definition. So, I never come to

care about her. Beyond that, close

friends each contribute something to the relationship the other needs; if I’d

known what the protagonist lost with her friend, I would have felt the loss as

it happened.

Jandy

Nelson has me caring from page one:

This is how

it all begins.

With Zephyr

and Fry –reigning neighborhood sociopaths –torpedoing after me and the whole

forest floor shaking under my feet as I blast through air, tree, this white-hot

panic.

In these two sentences I

come to know about care about Noah.

Because he is running from bullies, I feel immediate sympathy for

him. I smile at his voice, at his

hyperbolic way of thinking, at his energetic, racing syntax. I also admire my first glimpse of Noah’s

vivid way of viewing the world. If

Nelson can do this in two sentences, imagine how much I, the reader, care about

Noah by page 145 when Jude describes Noah’s new, non-painting personality as

“death of the spirit”. I literally

gasped. I felt the loss, because I’d

been given a chance to feel what Jude was losing. I lost Noah with her.

The Readers’ Job

In

one of the final scene of Nameless Novel, one character basically explains the

meaning of the entire book, over the course of eight pages. No fair.

A book is supposed to be an interaction between the reader and the text. It’s the author’s job to put a story out

there. It’s the readers job to react to

it. No fair kicking the reader out and

taking over that role. A significant thematic

line or two placed appropriately? Okay.

But eight pages. It kicks me

right out of the story because I have no more thinking to do. And, frankly, it feels disingenuous because

in reality nobody shows up to explain the meaning of life.

To

be fair, even Nelson dallies with the temptation to moralize at the end of I’ll Give You the Sun, but at least her

thematic lines are tied to in-scene action.

It’s a little much when Jude rambles on about how maybe we are

accumulating new selves all the time, but this is so incredibly overshadowed by

action-action-action at all the climactic moments. Jude saws the NoahandJude statue in

half. Oscar tackles Noah. Guillermo realizes Dianna is Jude’s mother –not

because someone tells him – but because he sees

the studies for her statue. This is a

novel of secrets revealed, but they are never just disclosed from one character

to another, they are revealed through action every time.

I

hoped by exploring the contrast between these writers’ approaches I would be

able to arrive at some general principle of novel writing that embodies all

four of these writing musts:

•

Staging characters’ essential discoveries through action achieves the integrity

at the core of why we write in the first place.

•

Heading directly into the messiest moments at the emotional core of the

material results in radically true, reader-changing moments.

•

Slowing down and spending the time to develop characters who need each other

raises the stakes, heightening the moments when we lose them.

•

If you do these things, there won’t be any need for you to explain your book’s

meaning in the final chapters because your readers will have lived it.

I think all of this can be

summarize by some of the most powerful words a writing teacher ever shared with

me. Editor Patti Lee Gauch often says,

“Go far enough.” I’ll Give You the Sun is a prime example of a writer going far

enough.