Spend the necessary time with your premise.

Words from wise writing

teachers. This summer I’ve taken them to

heart. Most mornings I sit down with a

chocolate croissant, a cup of coffee, and Donald Maass’ Writing the Break Out Novel Workbook and learn something more about

my characters, their conflicts, and their building tension. It’s the middle of July, and I don’t have

many pages. You know, actual pages of

the first draft. Well, I have one I

wrote this morning. But, in six weeks,

I’ve made more progress with this story than any of my other novels.

I think it’s because I’ve

been working on the distinctions Maass makes between the protagonist’s main

problem, and what he calls complications, plot layers, and subplots. Maass uses a lot of adult novels to

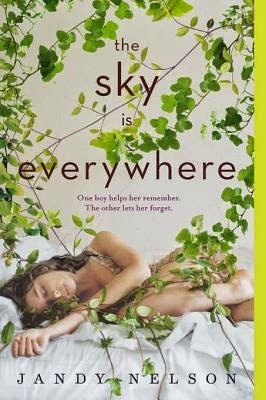

demonstrate these concepts, but I’m going to use Jandy Nelson’s The Sky Is Everywhere here to illustrate

them. I think Nelson’s understanding of

how these elements work in her story account for the fully-felt reading

experience.

Warning: Spoilers Abound!

Look, The Sky Is Everywhere could easily have turned into another great

YA example of “girl must choose between Edward and Jacob.” Lennie is caught between a romance with her

recently dead sister’s boyfriend, with whom she can remember and grieve the

past, and the new musical genius in town, with whom she can imagine and

celebrate the future. But the book is so

much more than that. And here is why.

No surprise, Nelson is

crystal clear about Lennie’s MAIN

PROBLEM. And it is not just a choice

between to boys. Lennie wants to get

through her grief for sister, Bailey.

Her Uncle Big actually says, “There’s no way but through.” What that means gets complicated though. Through

means time to experience loss and pain, and through

means being on the other side of loss and pain, able to embrace life again.

Maass defines COMPLICATIONS as the obstacles that get

in the way of the protagonist’s main goal.

These not only abound in The Sky

Is Everywhere, but remain incredibly focused on Lennie’s desire to get

through her grief. Toby, the now-dead

Bailey’s boyfriend, helps Lennie remember Bailey in a way no one else can. Joe, the new boy in town, and perfect

counterpoint, enables Lennie to forget her grief. The jacket copy doesn’t lie when it reads,

“though she knows if the two of them collide her whole world will explode,”

because when Joe sees Lennis kissing Toby Lennie breaks with Toby and Joe

breaks with her. Without either boy in

her life, Lennie comes to realize that both relationships were masking her need

to face that, without her sister, she is undeniably alone. After this realization, it dawns on Lennie

she has been focused on only her own grief.

So well does Nelson understand Lennie’s main problem that the

complications can unfold and unfold.

Now Maass distinguishes

complications from PLOT LAYERS,

which he defines as additional problems the protagonist faces –not

complications to the main problem, but altogether different problems. Lennie has these too. She has avoided her clarinet talent. She writes audience-less poems which she

scatters everywhere. And Lennie learns

about her missing mother. These problems

exist separately from Lennie’s need to get through her grief, but they are both

compounded by Bailey’s death and come to inform Lennie’s journey through her

grief. The layering leaves Nelson levels

of problems to utilize in Lennie’s inner arc, but because she finds nodes of

conjunction between these layers and the main problem, the book holds

together. The layers are not random or

scattered, they are purposeful. If they

do not exist because of Bailey’s death, they become touch-points that help

Lennie make sense of things.

SUBPLOTS,

Maass says, are something else. While

plot layers are given to the protagonist, subplots are narrative lines given to

other characters. Nelson nails these as

well. Toby wants to hold on to Bailey, though he must let her go. Joe wants an all-or-nothing romance, but life

is more complicated than that. Gram

wants to talk about her own grief with Lennie, Big wants to bring the family –particularly

Lennie— back to life, and Lennie’s best friend, Sarah, just wants their

friendship back. Each character is

working to solve his/her own problem while the protagonist is working on the

main problem, though, again, the secondary character’s issues are tightly woven

to that main problem. The result is not

only a rich dynamic between characters, but also a meaning-making aesthetic.

The depth and breadth of

Nelson’s work with the protagonist’s main problem, complications, and layers,

as well as, the secondary characters’ subplots is encouraging to my work this

summer. Of course, it’s nice when the

pages start to come, the actual pages of accumulating chapters, but Nelson’s

work tells me something different. It

tells me it’s worth taking the time to understand your material with clarity.

I copied this quotation from

The Sky is Everywhere down in my journal:

Beside me, step for step, breath for

breath, is the unbearable fact that I have a future and Bailey doesn’t.

This is when I know it.

My sister will die over and over again

for the rest of my life. Grief is

forever. It doesn’t go away; it becomes

part of you, step for step, breath for breath.

I will never stop grieving Bailey because I will never stop loving

her. That’s just how it is. Grief and love are cojoined, you don’t get

one without the other. All I can do its

love her, and love the world, emulate her by living with daring and spirit and

joy.

The reason I catch my breath

when I read this passage is because Jandy Nelson earned that moment. She earned that moment because she took the

time to know her material with intense clarity.

I’m going to do that too. Thank you, Jandy!

No comments:

Post a Comment