So I’ve spent the summer

exploring the premise for a new manuscript, and this has included a lot of

plotting. Plotting for me is a

combination of note-taking alternated with exploratory writing. But plotting before a first draft can only go

so far. There are some anchor points,

like the climax, which I can already visualize, but there are others, like my

protagonist and antagonist’s momentous turning point. A moment like this I am sure should be

realized through an overt action, but I just don’t know what it should be

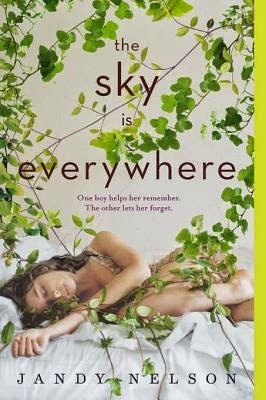

yet. So I thought I’d reread the crown

jewel of YA novels which realize important plot moments through overt actions

–Jandy Nelson’s The Sky Is Everywhere.

As always, this post is full of spoiler

alerts, but if you haven’t read TSIE, you should stop reading this and go get

the book immediately anyway!

I could write a doctoral

thesis on the countless ways Nelson uses characters’ overt actions to realize

key plot moments. The characters’

interactions with plants, Lennie’s poem-writing, Gram’s box of letters to

Lennie’s mother, and, of course, Lennie’s relationship with her clarinet are

just a few. Notably, each time a character

executes an overt action, it is attached to a motif like the plants, poems,

letters, or clarinet. So much so that

I’ve come to think of them as motif-actions.

For this post, I’ll focus on what Lennie does with her beloved copy of Wuthering Heights. Interestingly enough, this is also a turning

point scene.

After her ploy to cut a

bouquet of Gram’s prized roses fails to win Joe back, Lennie is finally having

her heart to heart with Gram. Lennie

realizes how foolish choices, including her own, prevent us from experiencing

great big love while we can (Life is short.

For Bailey, it is already too late.)

But Lennie and Gram don’t just talk about it; Nelson realizes this

turning point by having Lennie execute an overt action. Lennie uses Gram’s garden shears to chop up

her copy of Wuthering Heights. This is Lennie’s favorite book, annotated and

dog-eared over twenty-three readings! Here is what I learned by

highlighting all of Jandy Nelson’s references to Lennie’s doomed novel.

First, when it comes to big

motif-actions like this, Nelson seeds them almost from page one. The first reference to Lennie’s Wuthering Heights is right at the top of

page two where she is scribbling a poem in the margin as Gram and Big worry

over the Lennie plant.

Second, Nelson’s use of

Wuthering Heights is never forced because she takes the time to establish

Lennie’s relationship with this book.

Lately, a lot of YA characters seem to have favorite classic books

guiding them, but Nelson’s use is by far the most believable because she

establishes Lennie as a literary person.

On only page seven, Lennie describes her best friend, Sarah, as a

literary fanatic like her, delving into Sarah’s darker reading tastes.

Third, Nelson uses Lennie’s

interactions with her copy of Wuthering

Heights to create an arc of development.

Early on, Nelson uses road-reading to establish Lennie’s starting point:

“I like love safe between the covers of my novel.” As Lennie’s experiences with Joe and Toby

compound, her comparisons of real-life erections and kisses with the Wuthering Heights world are funny. The book also becomes a vehicle for Lennie

and Joe to get to know each other over lunch in a tree. Later “Heathcliff and Cathy have nothing on

us.”

Fourth, I learned that once

you find that motif-action for your big moment, extend it further than you

imagine you can. After Lennie chops up

her Wuthering Heights, she rakes her

fingers through the remains while ruminating on her regrets. As the conversation with Gram continues, she

wants to scoop a fistful of book scraps to throw at Gram. She also rearranges the words into new

sentences, reflecting the mood of the moment: under that benign sky and so

eternally excluded. Then she wishes

she could put the words back together so Cathy and Heathcliff could make

different choices. Finally, as her

understanding of life and love has evolved far beyond the novel, Lennie sweeps

the whole thing into the trash.

Fifth, by watching Nelson I

learned to look for ways motif-actions can cross subplots. After Lennie chops up her book, she hands the

shears to Gram, and Lennie sees Gram has her own reasons to be angry. Gram also has her own reasons to be ashamed,

which we see as she sweeps the book scraps toward herself. The pile of scraps jumps when Gram pounds the

table with her fist forcing Lennie to hear her reality. Later, Lennie writes a poem in which Cathy

and Heathcliff’s stronger-than-death love becomes about Lennie and Bailey. So as motif-related actions cross subplots,

their meaning reverberates out across the story.

The last thing I learned may

be the most important of all. I’ve

written enough to imagine Nelson developing Lennie’s growing relationship with

her copy of Wuthering Heights. I’d bet Wuthering Heights popped up in a

freewrite about Lennie, maybe just a matter of characterization. As Nelson continued drafting maybe she saw

opportunities to draw Wuthering Heights

through. Maybe she even took a break

from the story to write about what Wuthering

Heights meant to Lennie. Maybe the

image of the shredded pages occurred to her then. Maybe during revision, she played around with

the remains of the book left on the table.

Maybe she went back and reread Wuthering

Heights, wrote about Lennie’s favorite book some more, and realized how it

applied to her relationship with Bailey.

Whatever the case, as long as I keep looking for the motif-action that

could become my turning point, as long as I keep mining my current draft for

accidental gems, as long as I keep journaling about my characters, it’s okay to

proceed without knowing exactly what that turning point’s overt action will be.

Observing

Nelson’s use of Wuthering Heights has

taught me something about the nature of the overt motif-action. Like any seed, you can’t force it to grow,

you have to keep nurturing the soil, and it’s definitely worth waiting for. So thanks, Jandy, for freeing Lennie and for

freeing me!